Normalisation of alcohol use

Normalisation of alcohol use refers to the widespread availability and social acceptance of alcohol in Australia. It also includes the social acceptance of getting drunk or drinking at risky levels.

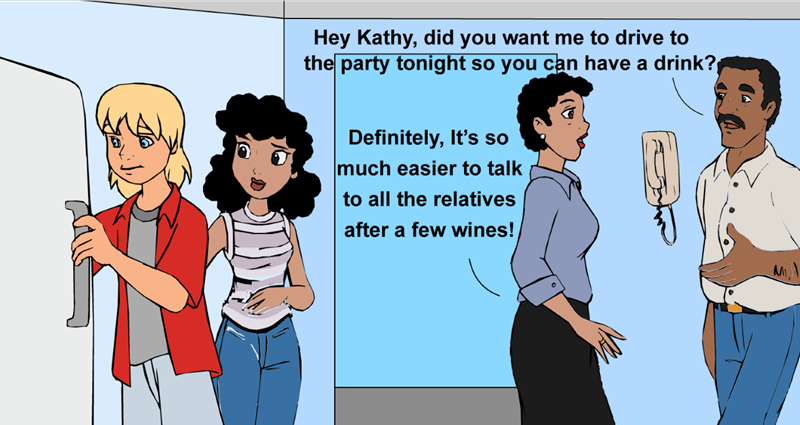

In Australia, alcohol use is a regular part of society, with alcohol consumption common at social settings, parties, sporting events and celebrations both inside and outside the home. These celebrations can be particularly common at the end of the year, with family gatherings and New Year’s Eve. Young people are often exposed to alcohol through advertising, the widespread presence of alcohol outlets (pubs, bars, clubs, bottle shops), social media, and on TV shows or movies. Alcohol advertising not only appeals to those under 18 years, but can also influence their alcohol purchasing behaviours. Additionally, exposure to positive portrayal of alcohol use (e.g. at parties or dinner) via TV and movies is associated with binge drinking at a younger age and higher consumption of alcohol both in adolescence and later life.

Alcohol use can also be portrayed as a coping strategy. While it is not unusual to reach for a drink after a stressful day, for parents this practice can have unintended consequences, affecting how your children view alcohol use. Memes or advertisements about the use of alcohol as a coping strategy can further normalise alcohol use and promote a harmful drinking culture where drinking to excess is seen as 'normal' or 'funny'.

How does parents’ normalisation of alcohol use impact children’s use?Home is where many Australians drink alcohol. When asked where they usually consumed alcohol over a 12 month period, 79% of adults reported their home and 43% said a friend’s home. Drinking at home can mean children are likely to be familiar with their parents’ or other adults’ drinking behaviours, which can result in alcohol being normalised in young people’s lives, long before they reach legal drinking age. Additionally, children and teenagers look to parents to model their own behaviour, and so they may imitate their parents’ behaviours and attitudes towards alcohol, for example by drinking alcohol to cope with stress, have fun or to boost self-confidence.

Research shows that parents’ drinking behaviours influence when adolescents start to drink and how much they drink. This means that by modelling behaviours like drinking to relax or getting drunk at social gatherings, parents can inadvertently reinforce positive attitudes towards alcohol or towards getting drunk.

The good news is that parents can help young people to develop healthy attitudes towards alcohol, by drinking in moderation and/or modelling ways to turn down a drink. Parents can empower young people by demonstrating that social gatherings do not need to revolve around alcohol, and by modelling ways to have fun without alcohol. It is also important for parents to model and discuss with children alternative and healthy coping strategies during tough times.

Importance of delaying alcohol consumption in adolescentsThe brain undergoes significant development during adolescence that continues until the age of 25. Therefore, adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the harms from alcohol, and delaying alcohol use for as long as possible should be the goal. Some of the risks associated with early initiation of alcohol use are:

- Increased heavy alcohol use in older adolescence.

- Greater likelihood of developing an alcohol use disorder later in life.

- Increased risk of other drug use.

- Increased risk of developing mental health related problems.

- Disruptions to brain growth and neurochemical functioning.

- Poorer school performance.

- Risky sexual activity.

Tips to avoid normalisation of alcohol and model responsible drinkingBelow are some strategies to help parents’ model responsible drinking.

- Limit your alcohol consumption, especially around children.

- Avoid getting drunk, especially in front of children.

- Offer non-alcoholic drinks at family occasions and events.

- Openly turn down offers of alcohol in front of your children.

- Demonstrate that social occasions can be fun without alcohol.

- Never drink and drive or allow other adults to.

- Model some healthy strategies to cope with stress such as going for a walk or listening to music.

For more information check out this factsheet on how parents can protect against drug and alcohol use and related harms.

Evidence BaseThis factsheet was developed following expert review by researchers at the Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney.

- Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting Factors Associated with Reduced Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44(9):774-83.

- Roche AM, Bywood P, Freeman T., Pidd K, Borlagdan J, Trifonoff A. The Social Context of Alcohol Use in Australia. Adelaide: National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction; 2009.

- Aiken A, Lam T, Gilmore W, Burns L, Chikritzhs T, Lenton S, et al. Youth perceptions of alcohol advertising: are current advertising regulations working? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2018;42(3):234-9.

- Carrotte ER, Dietze PM, Wright CJ, Lim MS. Who ‘likes’ alcohol? Young Australians' engagement with alcohol marketing via social media and related alcohol consumption patterns. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2016;40(5):474-9.

- Azar D, White V, Coomber K, Faulkner A, Livingston M, Chikritzhs T, et al. The association between alcohol outlet density and alcohol use among urban and regional Australian adolescents. Addiction. 2016;111(1):65-72.

- Koordeman R, Anschutz DJ, Engels RCME. Alcohol Portrayals in Movies, Music Videos and Soap Operas and Alcohol Use of Young People: Current Status and Future Challenges. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47(5):612-23.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022-2023. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare,; 2024.

- Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education. 2020 annual alcohol poll attitudes and behaviours. Australia; 2020.

- Gilligan C, Kypri K. Parent attitudes, family dynamics and adolescent drinking: qualitative study of the Australian parenting guidelines for adolescent alcohol use. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):491.

- Fagan AA, Najman JM. The Relative Contributions of Parental and Sibling Substance Use to Adolescent Tobacco, Alcohol, and other Drug Use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(4):869-83.

- Parenting Strategies. Be a good role model 2020 [Available from: https://www.parentingstrategies.net/alcohol/be-a-good-role-model/.

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Tessner KD, Toga AW. Mapping continued brain growth and gray matter density reduction in dorsal frontal cortex: Inverse relationships during postadolescent brain maturation. J Neurosci. 2001;21(22):8819-29.

- Bolland KA, Bolland JM, Tomek S, Devereaux RS, Mrug S, Wimberly JC. Trajectories of Adolescent Alcohol Use by Gender and Early Initiation Status. Youth & Society. 2016;48(1):3-32.

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, et al. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):109-18.

- Baiden P, Mengo C, Boateng GO, Small E. Investigating the association between age at first alcohol use and suicidal ideation among high school students: Evidence from the youth risk behavior surveillance system. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;242:60-7.

- Lubman DI, Yücel M, Hall WD. Substance use and the adolescent brain: a toxic combination? J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(8):792-4.

- Peleg-Oren N, Saint-Jean G, Cardenas GA, Tammara H, Pierre C. Drinking Alcohol before Age 13 and Negative Outcomes in Late Adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(11):1966-72.